My Bridge

(An Ohio journey- with Henry Thoreau. Station Road Bridge, Brecksville Ohio. A Notebook reminiscence)

While visiting relatives in my home state, Ohio, over a holiday, I found myself unable to sleep.

So I opened the book I had brought in my carry-on: A Week On the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, by Henry David Thoreau.

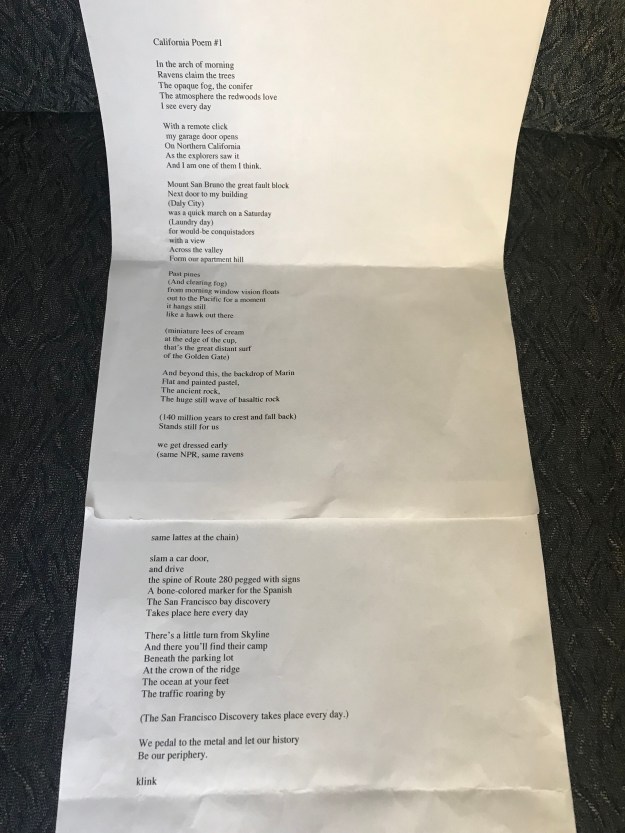

Why couldn’t I sleep? After a plane flight from San Francisco, Ohio is three hours ahead of California, so perhaps that was three extra hours to stay up and think.

As a dear uncle had said pointedly, “Keep digging that trench!” -Meaning that perhaps I wasn’t really getting ahead in my little bookstore life in those days.

So, Thoreau.

Reading Thoreau wasn’t an act of individualism, or a rebellion against a conventional attitude, no different drummer thing. I just wanted to get some sleep.

I was reading as a reference to a recent article by John McPhee, which a friend had given me to read on the flight to Ohio.

This was an article in Atlantic Monthly; an account of author John McPhee’s journey retracing the route of Thoreau and his brother along the local rivers and canals in Concord, Mass. in 1839.

It inspired a re-reading of A Week on the Concord and a Merrimack Rivers- Thoreau’s first try at his new style, to be perfected in Walden or Life in the Woods.

It was a perfect Ohio book, since my holiday visit included long drives through the countryside, around the woodland parks of the Cuyahoga Valley, and walks with my sister and family along the river and down by the old Ohio and Erie Canal.

***

The Thoreau book is a favorite of mine, though my memory/retention is not that great, and my understanding of its Transcendentalism less than perfect. I had first read it shortly after the deaths of my parents in the 1980’s, only a few years apart. Natural causes.

Thoreau wrote A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers as a requiem to his brother who had just died: a memory book about their journey together by boat, by river and canal in 1830’s. A series of day trips, really.

While I was reading A Week for the first time, I had I become curious about the natural history of the country, the age of the rocks around me.

Earth had become of greater interest to me after my parents’ death, and nature seemed to interact with the feeling of loss I felt.

Grief can focus the senses. One looks at life in a new way. It is the shock of the new, to borrow a phrase, to go on living. One may look to the natural world, or to the thoughts of others, for a way through.

One looks for a bridge of some sort, and finds it in nature, perhaps, or in a book.

A critic of American letters called Thoreau the great poet of loss. I can’t remember who. Does it matter? It’s like three am here.

***

Thoreau’s writing is luminous with grief. There is humor, also, in his writings, often overlooked. It’s obvious he was incapable of telling a joke, and these fall flat in his books, but when he directly engaged his audiences at his lectures with descriptions of themselves -they laughed; his delivery was spot on.

But A Week, written after his brother’s death (natural causes) shortly after their river trip, that was elegy.

Behind it all, a deeper motive; his meditations as he journeyed through landscape are not idle musings. They reflect an interest in the history of the landscape and all its inhabitants as a way through grief.

In A Week he is preoccupied with the past, both ancient and the local: fragment of poetry, or an arrowhead found by chance. Or by the fading of one simple day into another; the principle of loss and reflection is in each case the same.

***

In his book, Thoreau seems to wander, to ramble, yet his writing requires a rapt attention to follow the path of his thought.

Not all his sermons hold interest. One reads on until the writer describes with perfect accuracy his surroundings, or reveals, as a great teacher, the living art of the ancients as part of his own elegiac artistry.

Homer, the poets of Classical Greece or the scriptures of India, the Sutras- I know nothing of these, but gain something, as I read A Week. It is perfect to carry on a trip, or to read when one can’t sleep.

***

The critic Alfred Kazin notes that Thoreau did not survive the Civil War. He posits that the world of Thoreau did not survive, either.

Thoreau died of tuberculosis in 1863. He worked on his nature writings, perhaps as a counterbalance to the thought of war. Of course he had weighed in on the political issues of his day, his personal activism a matter of record.

But during the Civil War he became deathly ill. While he still had the strength, Thoreau resolved to travel, seeking improvement in the natural environment of the West. He made it to Minnesota and back.

He knew his journey might be final: on a Missouri River steamer in 1862, Thoreau heard the steamboat’s bell struck three times at the bustling dock and noted the dire sound, even wrote it out, its mournful clang.

***

In his last trip he wished to see the Indian People in their “natural” environment, but the performance he saw was already stage-managed by, and for, whites. He saw buffalo, but not the great herds, and as for flora and fauna, he was too weak to fulfill his Nature wish-list. His notebook is sparse. He returned to Concord with only a few months to live.

Still in his house were stored the hundreds of unsold volumes of A Week, his first book, which after his death were yet unbound. These upon his death were finally bound and sold to a belatedly interested public, decades later.

These posthumous second editions of A Week are, somewhat ironically, more valuable than the first editions to collectors, due to their earlier provenance.

***

My dear uncle’s teasing, while irksome, is accurate. I really didn’t do my life very well at all. Prone to addiction, perhaps a little anxiety and depression: of course I had been in a rut. I was somewhat awakened though, when I saw the potential of my week by the Ohio and Erie Canal, in terms of entwined meanings, as Henry Thoreau would have pointed out.

***

Somewhat bitter, pondering a lost world and missed opportunities, like the canal that was obsolete upon its completion, I pondered a quaint picture of the pastoral wealth of the past; the hopes and optimism, here and there placed like historical markers, put me in a better mood. I’m not upset or nostalgic, but realistic. As did Thoreau, I look both ways in the modern world: to the ancient past, insofar as it exists with us, and to the presence of the future in the present. Or whatever.

I’m awake now. And not in the insomniac sense: Awake.

***

In Ohio for a week, reading the river and canal journey of Thoreau, I became curious about the Cuyahoga River and the beautiful countryside near our home town out on Riverview Road, out by the old canal. My family, along with my sister’s yellow Labrador, Chewey, went for a drive to have a look.

The river flows beneath a giant span, an impressive high level bridge of arches, across a chasm that is perhaps four hundred feet deep; its valley is a broad flood plain that contains a railroad, a little yellow station by the tracks, and the wide river.

Along the east bank of the river are the remains of the old Ohio and Erie Canal. Over the canal is a small iron bridge, perhaps fifty feet long. When we got to that little bridge, the yellow lab Chewey stopped walking and refused to cross. He got part of the way, looked down and would go no further.

“Chewey doesn’t like bridges,” said my twin sister. “We aren’t sure why.” So we had to carry the big goofy dog over the historic little bridge like a sack of potatoes.

He endured the indignity grudgingly, his big eyes rueful, staring forward, his toenails nearly dragged along while I hefted him over, hugging the heavy dog as in some unfortunate Heimlich maneuver, until we got half way over the bridge and he was willing to go on his own. “C’mon, Chewey!” I was muttering, to no avail.

Bridges. Transitions. Don’t look down, Chewey. We’re almost there.

I’m not much better at transitions.

Neither is my twin. A mom of two, a teacher, she meets the demands of many roles, but partings leave her bereft.

As for myself, associated with the canal are metaphors and cliches that may well suit this writer’s history: I’ve been bogged down; I’ve barely scraped by. Going ‘round the bend. Etcetera.

And with us, our niece Molly, age 17, just recruited by the US Marine Corps. It’s our last relaxed visit before boot camp, and then who knows what, with the US at war now. She was bored by the little river, anxious to get moving. We won’t be long with this history thing, we promised. We walked along as a family, past the bridge, along the river.

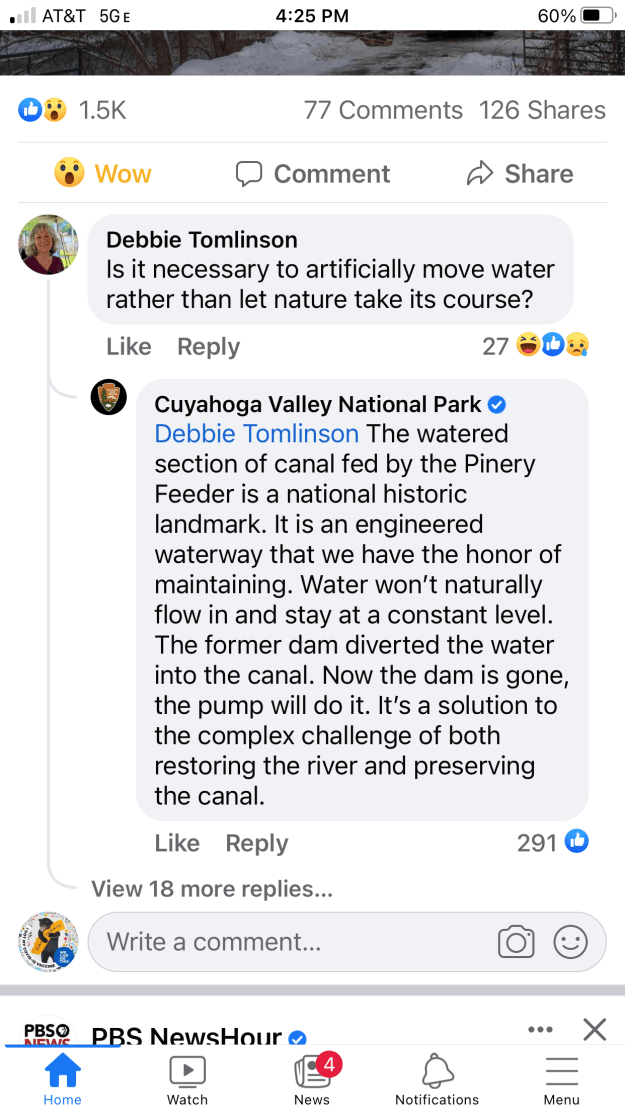

Chewey’s bridge is adjacent to a section of the old canal. Here the mighty Cuyahoga, full to its banks from recent storms and melting ice, roars over a spillway.

Chewey’s little bridge, dwarfed by the high level bridge above the wide valley, crosses over a small section of a feeder canal, which once regulated the flow of the canal proper, which is just a few yards beyond it, and is now a culvert of sticks and leaves adjacent to the river.

The bridge is the first of its kind in the state, made of iron girders 150 years ago, as we were informed by a little park sign. Nearby, one stone piled upon another, is an artifact at the culvert’s edge.

The Thoreau brothers boated and camped along features such as these, on their final river/canal journey of A Week in 1839, and Thoreau noted them all with great interest, as he did buried stones, abandoned sites, and artifacts of early inhabitants.

Here in Ohio, on a little muddy slope, was all that was left of a bit of canal infrastructure, a small pile of rocks, left in place, in mud and leaves, a relic of history.

The section of canal beneath Chewey’s little iron bridge represents the usual specification for river traffic in the 1830’s: forty feet across, four feet deep, twenty six feet across at the bottom.

So in this, it looked just as it should on the day of its completion.

The Ohio and Erie Canal was opened on a July day in 1827 when Gov. Trimble travelled from Akron past this very point on up to Cleveland on the boat “State of Ohio”- a more dignified presence than ours, carrying the dog, but no less respectful of the surroundings.

The canal had been responsibly legislated and financed, in its day.

Although 16 million dollars that it took to create Ohio’s canals nearly bankrupted the state, according to one source, the debt was paid off in time for the flood of 1913 which damaged enough of the Ohio and Erie Canal that it was ruined as a going concern. Its peak revenue year was 1851, in the era of Thoreau’s Walden, and by that time the railroad’s cheaper rates threatened the canals’ economic survival. Though a price war was forbidden by state law, the railroad flauted it and the canal’s day’s were numbered.

The railroad was delayed, however, for the topography of the valley hindered its development. The hills were steep shale and unpredictable, and conditions on the valley floor were not much better.

The railroad didn’t really compete until the last decades of the nineteenth century, when the demand for coal in Cleveland could only be met by the railroad. The region stayed pretty wild in the meantime. It was the canal which drew pioneers to the region, in the first stage of the state’s development, the canal right near our little Ohio town.

These conditions concur in Thoreau’s locale in the same era: his canal he and his brother paddled down was nearly out of service in his time, due to the new railroad.

***

Stepping back from the old Ohio and Erie Canal- and back in time- we have the river valley gouged out by the receding glacier a few thousand years ago. The turnpike spans the high level bridge, above our little canal ditch, and follows the ridge, once an animal trail and the track of the old Indian pathway adjacent to ancient Lake Erie- a history which goes back 14,000 years. And beneath, the little train station and the little iron bridge.

Chewey could care less. “C’mon Chew, lets go, boy!”

George Washington himself had dragged a forefinger along the rough map north to south, proposing the canal which would connect the Great Lakes-all of them- to the Ohio River, right by this spot, and on down the Mississippi to the sea again. The infrastructure would include Erie Canal to the east coast of America, and so connect the entire United States.

High stakes indeed for Chewey’s little ditch of leaves this winter day.

***

So we took a picture. I have it here before me, of my family, all smiling, winter holiday, 2003. Everyone healthy, thank God, smiling, standing at what was once the very westernmost edge of the United States.

And behind us, the great bridge, with its concrete spans, arches which, reflected in the river below, complete a circle. Bridge, and history, and family connections, and even my ineffectual life all have a place here, right here now. Smile!

The picture is dominated by the roaring turnpike bridge behind us, but to the right and almost out of the picture is the little iron bridge, the first iron bridge of its kind in the region.

It’s the little history bridges I revere, the ones Chewey and I are afraid to cross.

-Oh, on the way home we saw a deer.

jk

San Francisco

6-25 -04

***

Just a reminder to all: the RR tracks north of Station Road/Brecksville Station are still closed due to eagles trying to raise their young.

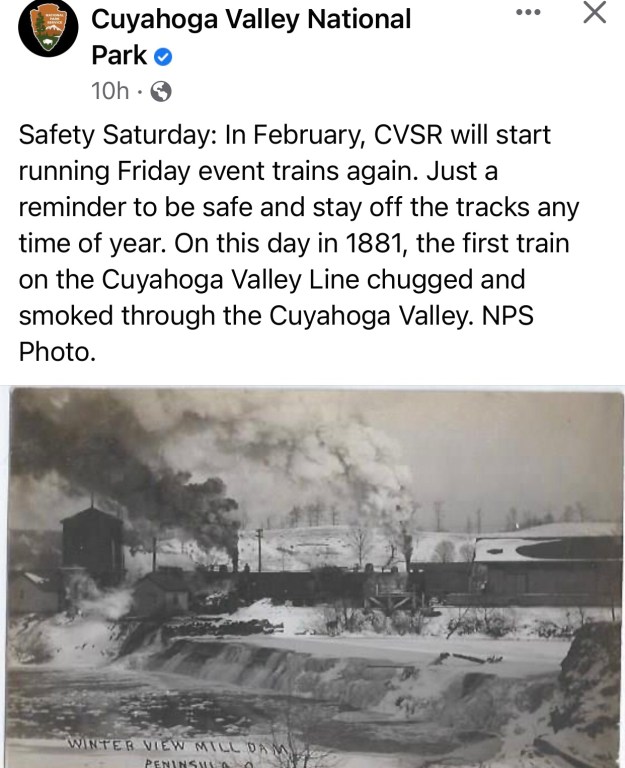

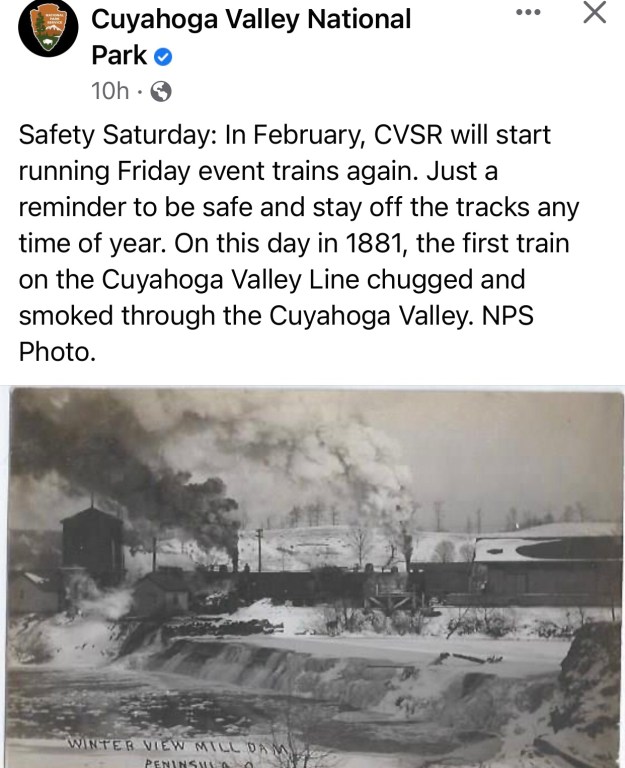

#TBT: Today in 1880, the new Cuyahoga Valley Line was in its second day of service, linking Cleveland with the coalfields of Tuscarawas County through the Cuyahoga Valley. This Saturday and Sunday, passengers can still ride through a pastoral landscape in the valley on that same line, but in heated comfort. For ticket info, see http://www.cvsr.com Image courtesy K. Summers.”- Facebook post for CVNP

***

We picked Gingerbread House Day to reveal our 2022 #GreatNPSBakeOff entry. This scene celebrates a milestone in the Cuyahoga River’s recovery. In May, scientists caught the first bigmouth buffalo ever recorded in Akron. This long-lived native fish was able to swim upstream from Lake Erie after two dams were removed in the national park in 2020. The dams used to divert water into the Ohio & Erie Canal near the historic Station Road Bridge, shown in sparkling silver. Once so polluted that it burned at least 13 times, the Cuyahoga River now supports diverse wildlife, including bald eagles and river otters. Explore the Station Road Bridge area in person or virtually at https://www.nps.gov/cuva/planyourvisit/explore-the-station-road-bridge-area.htm. Help share this success story! Gingerbread and photo by Kelly McGreal, Conservancy for Cuyahoga Valley National Park.

***

Today in Cuyahoga Valley National Park history, the Ohio & Erie Canal National Historic Corridor was designated in 1966. Today, let’s take a moment to honor those that built, thrived and faced life’s challenges on the canal.

Pictured here is a northeast view across the canal, just below the mile 14 towpath marker at Wilson’s Mill. The boat was lived in by a repair master.

Cleveland Public Library Photo: A family stand on a canal boat, behind them is a large white colonial style building and a barn.

***

Life is a balancing act. As part of the Cuyahoga’s recovery, we try to give it space to flow where it wants. However, there are trails, roads, bridges, and train tracks nearby. To protect those, we have a major riverbank stabilization project in progress. The contractor is wrapping up north of Station Road Bridge. We’ll let you know when they move south. Native plants will be added later. Please continue to respect trail closures. Photos: Construction Support Solutions/Roberto Yaselli.