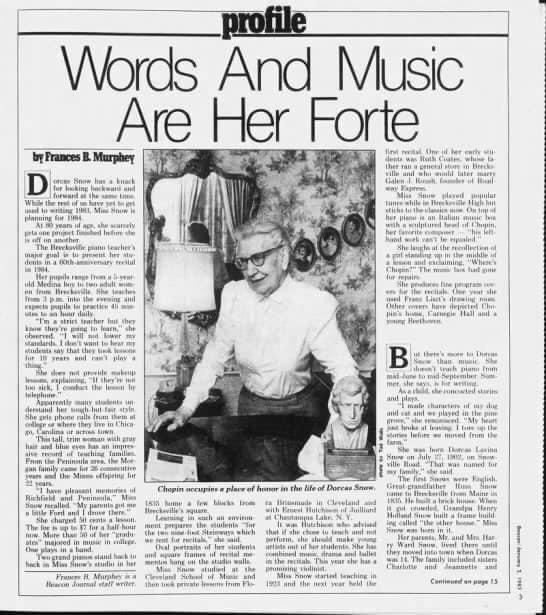

Miss Snow, my first piano teacher, Brecksville Ohio. It’s nice to find a good photo. She introduced students to Scriabin, Chopin, Rachmaninov, Liszt, Gershwin. She ordered music of Satie for me and looked at it and said : this man is a master of composition!

Satie had not completely resurged yet. Still pretty outre’.

By Satie she taught me “Premier Menuet, which isn’t. It’s 3/4 played in 4/4, with enharmonic scales in the apparently incorrect key, and with very little melody. So it’s not coffee commercial music-at all.

And Passacaile, by Satie, which is very modern and orchestral for him. Not Gymnopedies, like Blood Sweat and Tears made popular. She went right toward the outright strange pieces.

Exact opposite to her beloved god Liszt.

She had to order them. Rarity at the time.

The recitals were a big deal. For finales we had to play piano quartets, and we were loud on those 9 foot Steinways!

She said, “People may let you down- but if you have piano you always have something.” You’re never truly lost.

Her life: 1902-1994. She was my teacher during her 50th year of teaching, I think. 1973-5.

She completely analyzed structure and told us to practice in four rates, advancing through each: slow, moderate, allegro, and expressive.

She pushed Czerny hard, and scales; 2/3 of practice devoted to exercises and 1/3 to learning a recital piece. No piece was considered completely impossible.

She was also able to present the works of composers we thought were just strange, modern. Charles Wourinen. Schoenberg. Pieces that were made of arithmetic plus space, apparently void of content, all atonality.

She was very formal.

If you practiced, all went well.

***

Vexations!

Erik Satie!

Coincidences are mystical sign. They are.

So I’m at work tonight. Coincidentally, the cook, who I hardly know, working in the dining hall of our facility, is playing Erik Satie’s “Vexations” on his Pandora while preparing tonight’s dinner.

The droll theme to be repeated 840 times, according to the composer’s direction. Erik Satie. I heard many repetitions of the theme just in the last half hour.

That is devotion.

I didn’t tell him I listened to 42 repetitions just the other day.

We’re having mashed potatoes for dinner. Entree is pot pie. I was informed by a friend-just yesterday, as a matter of fact- that Satie preferred food that is white. Beef pot pie would be an infraction, a complete lapse of good taste.

I didn’t tell the cook that.

Today, again, coincidentally, before work, I organized my book storage downstairs in an effort to find my biographies of -Erik Satie. This had absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with tonight’s surprise kitchen Vexations.

I was thinking about my piano teachers, and the psychic advice received from “The Other Side” to practice my Satie.

And I stumbled upon the electronic moog performance of “Vexations” online.

Just coincidence.

“Vexations” is not a feel-good thing you’re going to punch into You Tube for no reason, that I can tell you.

I have ALOT of books down there in the storage locker of our garage- an entire library, in fact.

The biographies of Satie are all out of print, so you can pay forty dollars (or nine hundred dollars) for the five paperbacks I’m looking for down there with the spiders. They’re down here somewhere, I was thinking.

Found them!

It is a pure coincidence that the cook is a piano player and is practicing the Satie music at home, as he confessed to me when I asked about his playing “Vexations” this evening. If you were over at our apartment, you’d see everything Satie wrote in a pile by my piano.

I was playing “Prelude en Tapisserie” and “Passacaile” and “Premier Menuet” and other pieces this week.

Although I chose these at random from the photocopies, the latter two actually were beautifully printed sheet music of the first pair of short obscure piano pieces Satie wrote after a stint at a music school (mid-life crisis) to study counterpoint.

So, out of a hundred pieces, I picked these two obscure studies that belonged together. The twin musical products of intensive counterpoint, basic studies he undertook to make up for lost time, skills he never acquired in youth. Exercises. Just coincidence. These pieces are not well known. Critics say they’re not very “good.”

The Prelude en Tapisserie is translated as “Wallpaper Music.”

Love them!

This week- out the blue, from an Ohio neighbor we grew up with who is an antiques dealer, I received in the mail a rolled-up scroll in a cardboard tube: a vintage broadside to announce a memorial performance which occurred in 1925, the year of the composer’s death. It features the Cocteau pen and ink profile of Erik Satie and the list of featured performers on the program.

Satie. The poster: It’s lovely. The paper is microscopically thin. Must take care and get it framed properly.

Much of Satie’s music was initially published and recorded in our lifetime, not his. Posthumously, forty years after his death of cirrhosis in 1925.

It adds to the air of obscurity that still persists after a century.

So it came to pass, in 1968, all of the droll and mysterious and strange and vexatious output of this lonely aesthete became somewhat available to students. 1968, a year that celebrated counterculture, and so worldwide notoriety for Erik Satie.

So, we, of the Hip Era and the the Fin de Siecle, could popularize and assess and commercialize and perhaps even mystically divine the meaning of some of the strangest piano music anyone had ever heard before, out of school.

We heard records of course, but these were also the product of the latter-day 1968 publication of his complete piano work, in sheet music form.

Of recordings at the time would be a hit by Blood Sweat and Tears. And the multi- volume long- playing recorded works which ensued, by pianist Aldo Ciccolini, including the strange and experimental pieces and all of the notebook sketches they pulled out from behind, within, and on top of the composer’s old piano-and everywhere else in his studio after he had died.

But, most significantly among recordings of the sixties, early seventies, were the albums by Camarata Chamber Orchestra: “The Velvet Gentlemen” and “The Electronic Spirit of Erik Satie” and “Erik Satie Through the Looking Glass.” These featured Moog Synthesizer, but only in discrete sections.

The arrangements are unique and apt and appropriate, without overstatement or sentimentality. These are London label/ Derek Taylor productions, so grant the composer proximity to other “mod” recordings of Beatles and Stones and Rutles and Harry Nilsson.

The album covers and the liner notes are works of art, and contain a collage of the imaginative writings of Satie- and the recordings feature narrations by the composer, too. (Performed by another but true to the original.)

Those fascinating records, with their voluminous notes and graphic design, are out of print. Only fragments in You Tube. Sadly.

The French editions of the sheet music I lusted after were the original publications of Editions Salabert. My friend Jose “gave” several of them to me, in the early eighties of the last century. Others I gathered over the years as they became more available in book form. Everything was republished in recent decades. But Satie was a rarity in almost every form for a while.

My drinking buddy Jose played the violin and owned the newly issued and rare sheet music of Satie. How he got it all I never found out. He was a world traveler, so perhaps that accounts for the acquisition.

Jose’ was a drunk and a pool player who died of kidney failure after a night of pool and drinking (and whatever drugs Ronald Reagan had imported that year) at Finnegans Wake in Noe Valley in San Francisco, sometime around 1981.

This was by choice. Jose was sternly informed that his life would kill him but he said, I don’t care! He died happy.

The punk era had begun. New Wave, Brian Eno and Ambient Studies. And Satie was considered a pioneer of the New Music.

Perhaps he was the originator of Ambient Music, Minimalism, Kraftwerk, Punk, New Wave!

So, eventually those rare Satie pieces of sheet music came to me.

So it was a big deal to get something/anything at that time by this wonderful composer. Kids, we couldn’t push a button and instantly get music from another hemisphere in ten seconds. And ordering music from Europe? I don’t think so.

In the beginning, a post-sixties kid, with straggly long hair and jeans torn at the knee and sporting my Erik Satie t-shirt, piano lessons Tuesdays at 7:30 pm at the Snow house up on the hill, by the cemetery with the water tower.

So here we are forty years later.

I tell my wife Ingrid my Theory of the Afterlife, that when you think of someone or something it’s that person or thing calling you.

Listen.

Hm.

“Vexations”!

***

(This is just a dandelion…)

Summer: Bix Beiderbecke and Music in the Air

The boy wasn’t allowed to go down to the river, but on summer nights he could hear the music all the way to the house. It wafted in- calliope music, of all things, from the steamboats. Band music on the river. Early jazz in the early pre-dawn of The Jazz Age.

Music on a summer night.

There was more. There were the woody sounds of the family piano- his mother played and taught him a little. That was the music in the air.

Bix was a teen in the nineteen-teens, with his ear to the windup phonograph. He knew music by ear, note for note, though he learned jazz numbers rather laboriously, finding each note and chord on the piano. He was building the tunes, like a lot of teenagers since, ears to speakers, slowing revolutions of vinyl, to capture a tune they could run with.

So music on the piano would be heard in the air. The familiar, salutary sound of piano lessons in the neighborhood on a hot summer night, pre-World War One, Davenport, Indiana.

His piano teacher says he was hopeless.

A native genius from the start, he easily learned and remembered the music as he saw it and heard it, but learning by ear-and not by note from the printed sheet music- is the great stumbling block of piano students, for the super-precocious.

It would be the cornet, for Bix.

That was the instrument he brought to the Gennet studios in Richmond, Indiana, in 1924, with which he played the shining, clarion “bell-like” tones of great jazz recordings.

But as long as other musicians knew him, they would recall a piano composition he would often play. Stunning harmonics, a jaunty displaced rhythm, bright, yet restrained; thoughtful yet too brief- the piece might not have had a name at first.

I scan a biography of Bix Beiderbecke, and I find that the musicians around Bix- also true masters of jazz and orchestral performance- showed a spontaneous interest in being acknowledged by history as being among those who first heard the composition, and said it stuck with them, how impressed they were.

It was “In A Mist.”

“In A Mist” reminds one of Ravel. The title signifies jazz composition as modern art. It’s the art of compression, saying a lot in a short time.

Its rhythm, an underlying walking tempo, but with a touch of Picasso; parallel phrases ever so slightly displaced; a lighthearted exposition, as easy as conversation, all with the fluency of the artist thinking aloud.

It’s just three minutes alone with Bix. That’s “In A Mist”.

He demonstrates the art of writing, the improvisatory and spontaneous, with the carefully worked-out.

The beguiling puzzle of jazz: the practice, the mastery, of an art that defies note-writing- and yet, there it is on the page eventually.

You can’t write down ragtime, musicians used to insist. And the jazz that came after, which Bix himself played, of arrays of horns and banjos and percussion sections, with live recording paraphernalia, in primitive recording studios through the twenties, with the Paul Whitman Orchestra…

However intently that music attempted to write itself into sheet music charts, covering pop tunes and waxing light classics- it became something quintessential and unrepeatable in the hands of Bix.

There must be a copy of “In A Mist” in a piano bench somewhere. Have you heard it on a summer night? Like a rare bird alighting on your backyard bird feeder, you run to get binoculars and in a moment it’s gone.

It’s the close harmony that must have captured the attention. The bass, the parallel blues chords rising step by step, climbing the blues stairs, as the melodic voice sings lightly above; those mirroring dissonances sounding perfectly right, bemusing his fellow musicians who listened with a grin of interest and appreciation and delight.

What’s that called, Bix?

The biographer tells us they looked for a title and thought of “In A Fog”? “In The Air”?

No: In A Mist.

The piano piece has its place in the history of Jazz. Beiderbecke himself performed it at the pivotal historic Paul Whiteman performance debut of “Rhapsody in Blue” back in the twenties- a century ago,

Bix himself walked onstage alone to play the solo, a prelude to jazz, before an audience that included Rachmaninov.

The event represents a sort of official beginning to jazz as a form of classical music, which it now is. “In A Mist” is so inscribed into the very moment when the jazz era went BC to AD, entering its modern age.

The Beiderbecke piece was included in a program for the status quo, along with Gershwin in a premier which in retrospect perhaps threatened to legitimize jazz out of existence, to consign it to the brittle sheet music in piano benches everywhere, along with ragtime and the saccharine-sweet songs of the previous decades. But the modernism of the Twenties prevailed. And inspired.

Jazz had ever relied on the conventional and written, as well as the ingenious and brilliantly improvised, and the Gershwin rhapsody perhaps had found a sibling in Beiderbecke’s pioneering little prelude “In A Mist”.

Programs like the Whiteman concert are a summertime phenomenon. Orchestras will play the American music into the air on summer nights, in fairgrounds and amusement parks and on the Fourth of July in a bandshell, in a park by a lake- somewhere.

The tunes will waft over forest and river bluff and parking lot and cornfield.

And piano recitals coincide with the end of spring and the coming of summer. The neighbor kids may be practicing their pieces- at the last minute before Summer. It might be a bagatelle or invention. Or it might be a knotty Gershwin prelude, or a “theme” from “Rhapsody in Blue”. Maybe some ragtime. If your teacher will allow it.

Even sometimes one could hear a carousel with a refurbished calliope or orchestreon aboard, pumping circus carnival tunes- it’s still possible. Cotton candy still exists. And pastel and pin-striped salt water taffy. Summertime. Ice cream trucks, pinwheels.

All that will be so familiar, so nostalgic.

But it may happen that you’ll hear a harmony you’ve not heard before, or a musical idea will jump out, as on a cornet, bright and clear and new and rising quite above the fanfares and overtures, in a humble but ingenious individual voice. And you’ll remember it, and when you get home you’ll want to run to the piano and find that piece. Or find your own.

That was the beginning of the artist’s life, Bix Beiderbecke, in the early days of jazz.

And they are ALL early days.

jk

***

This little vid popped up on my feed and really got my attention.

https://fb.watch/icgjvtPsv3/?mibextid=v7YzmG

Our piano teacher in Ohio, Dorcas Snow, idolized Ruth Slenczynska. Miss Snow talked about her often. I believe she had a radio program out of Detroit, something like that. I have the impression there was a relationship there. Miss Snow certainly was devoted to her methods and outlook. She had her book of technique, I believe. There was a personal connection. I can’t remember the details now.

Miss Snow was the only classical instructor in town and taught for over 65 years. Whenever I see Ruth Slenscynska’s name I immediately think of Miss Snow.

Both were actively involved in radio, teaching, writing and performance in the Midwest. (Cleveland/Detroit/Chicago are really the same region- especially through radio at the time.)

Miss Snow was a taskmaster and insisted on total devotion and thorough preparation. She was also patient, and if you did the work she would grant you extra lesson time. I was devoted for at least a few years but a slacker half the time. Lessons were four dollars. 1972. I wore a suit jacket to my lesson. Seriously. It helped.

She taught me a Gershwin prelude, Beethoven- an early sonata, a John Field nocturn, Satie, at my request, a Rachmaninov Etude Tableau, and we played piano four hands and quartets as finales in recitals. Hungarian Rhapsody. We all played a Chopin etude too, note by note, phrase by phrase, four rates of speed. And we had to learn Czerny exercises and scales.

Miss Snow was training two brothers from Russia who were raised to be concert pianists. They played a massive repertoire. At least to our uninitiated ears.

Ruth Slenscynska also was connected to Lovejoy Library at S Illinois University, which was named after a famous ancestor of my second piano instructor, Allison Lovejoy.

There are interesting threads. Rachmaninov performed in the states and my great uncle Martin saw him perform and often told us his impressions of that peak experience. He was definitely the most influential musician in the piano world at the time. Miss Snow was a deep proponent of Liszt and Chopin and Scriabin. She did not mess around. She also taught pieces by Schoenberg and Wourinen- really abstract experimental music was fine with her.

To this day I play an hour or two most days. Just for pleasure. All I can say is Miss Lovejoy and Miss Snow taught me how to approach pieces so -if I want to- I can get things done.

I have a huge collection of music books so I can work on whatever moves me at the time. Nowadays I’m more likely to play music than to listen to recordings. I hear the music better when I’m playing it myself. I have some hearing loss and piano resonates really well and I can feel the music physically. It’s great.

I also like the feeling of being “inside” the music- when you’re involved in a piece you can participate in its inner workings, you can appreciate what it is. So instructors like Miss Snow and Miss Lovejoy make that deeper thing possible. It’s pianism, really, that they convey.

My grandfather had a band way back when, and he selected the pipe organ for the big Lutheran Church in Lakewood, St Paul’s. His son had engineering skills and built a clavichord out of a kit when he retired from teaching. My dad played clarinet in the army band and sang in the choir. Our parents sang us duets and lullabies when we were young.

Every house had a piano, most played piano rolls, too. So piano was everywhere and must kids practiced pieces constantly as summer recitals approached. You could hear pianos banging Tchaikovsky on both sides of the road in our neighborhood.

The ABC interview below is a delight. I’m enjoying it right now! Featured in mid interview is a languid Rachmaninov etude Allison taught me at the Community Music Center. It’s special.

I’m amazed at the deep well of expertise these teachers/ musicians bring to their students. Just to have a tiny fraction of that is such a tremendous gift!