Here’s a piece about “discovering” California. It’s only one beginning of many. From my notebooks.

***

A Monterey Discovery

(1602: Three ships, two hundred men, and their commander, Vizcaino, whose plans specifically included the attainment of personal fortune in pearl fisheries along the California coast, the discovery of which Spain would subsidize in return for a survey of a region crucial to the fortunes of Spanish galleons enroute to the Philippines and Japan.)

***

The elements are simple: green grass near the granite pillar, the border marked by a little white fence. Leafy trees and shrubbery fill what appears to be a gully at the foot of the Presidio hill.

One wouldn’t consider this generic spot “californian” but for the nearness of Monterey Bay, and the interest of its rocky shoreline as it curves past Cannery Row to the Point of Pines, beyond which the blue waters take on the granite color of the Pacific Ocean.

Yet this is the Discovery Site, the spot at which the explorer and entrepreneur Sebastian Vizcaino reconnoitered beneath a great oak tree, in 1602. His ship at anchor in what was in inlet, he surveyed by eye, recommending the harbor to future explorers, recommendations which were realized by Father Serra in 1770, when Empire Spain finally put forth the effort to develop the missions and trade routes of Alta California.

It’s not much larger than a parking space, the little corner of discovery.

The little hollow behind the fence reminds one of a vase of flowers with too many stems, overgrown and green. And, between the little hollow and this curbside, a small patch of mown grass. Though the foot-traffic of joggers and tourist passers-by is pleasant enough, the traffic of SUVs and compact cars beyond the curb is ceaseless. One crosses with the light, to visit the Discovery Site.

In some sense there is nothing to see here. One looks vacantly into the middle distance for some moments, listening to the traffic shushing by before it dawns that here indeed was the inlet where ships could approach and anchor, and boats might land. Yes, the gully is the natural drainage of the area right down to the bay itself a few hundred feet away. The great oak, the Discovery oak, the Vizcaino oak, is long gone, but today’s tree-covered ravine represents what was once a broad inlet near which ships were anchored. Now it is filled, cut off from the bay in order to build Lighthouse Drive, but beneath, it still runs to the sea.

Yes: above me is the broad hillside with its dramatic vista over Monterey Bay, where once existed a small, ancient cannon emplacement, the Castillo. And there, a few hundred yards away, is the curve of the bay itself. Right at the landing site it begins, trending eastward with its salient features of beach, Custom House, old wharf. Along and around its curves, east and north, the shore runs up to Santa Cruz, in the far bluish distance. That is the blue bowl of Monterey Bay. And to the west, Pt Pinos, the Pacific, Mission Carmel.

An estuary of fresh water is just a shot away, where now ducks serenely glide. Right here, a place for ships to land, refuel, repair. And

It’s a natural half-way point along the endless coast, which, for mariners, ran all the way from the Asian ports; they followed the linear coastlines of the continents, using the currents to their advantage. They did not cross the seas, but followed the land.

Vizcaino was among the earliest European explorers to leave a contemporaneous record, to recommend further exploration.

“It is all that can be desired for commodiousness and as a station for ships making the voyage to the Philippines,” wrote Vizcaino of his of what is now Monterey.

“In addition to being so well-situated in point of latitude…for the protection and security of ships coming from the Philippines.. the harbor is very secure against all winds. The land is thickly peopled by Indians and is very fertile,” he noted.

The Manila galleons of the fifteen hundreds were death ships, but for a harbor with wood and fresh water, re-provisioning and rest. Tragic fragments of China silk, porcelain shards were brought to the Spanish explorers when they’d land, handed over by the local inhabitants; instant archeology from a galleon wreck, the reminder of the likely fate of a larger percentage of every crew.

Monterey was a necessity, and its discovery was an expedient. That it represented the founding of California was only in retrospect: Who knew?

A complex exploration and vague cartographic history precedes us here. But it is the mariner Vizcaino, beneath his oak tree, which links Monterey to the beginning of its Spanish era.

Nearly two centuries passed for the huge oak tree, before the Spanish return.

***

The Vizcaino Oak is the mythic Plymouth Rock of California’s Spanish founding era, a founding relic that represents similar history of colonization, conflict, decay development.

Remnants of the tree by which the 1602 explorers moored do exist and are modestly displayed perhaps not as relics of the past, but as objects of curiosity, easily overlooked in two glass cases: one at the old Mission Carmel, and the other at the Royal Presidio Chapel, here at Monterey, not a mile from the discovery site where it once grew. The equivalent of small smudged type-written photocopies tells the story of the oak to those with the patience to linger. History itself becomes its own shorthand as one jumps back via 3×5 cards to 1770, when Serra, too, stood beneath this oak, one limb of which is mounted by the church door.

Visitors to the chapels founded by Serra find the Vizcaino oak fragments only by accident. I stood before a display case for long minutes at the Mission Carmel, wondering if that worm- eaten hunk of wood was indeed a fragment of the Oak. I had read that the entire oak was saved, and it was on view behind the first presidio chapel of Monterey, not far from the Quality Inn with the indoor pool where I was staying.

When I approached the chapel, I walked around past the redwood trees to the rear and found only roses. Fragrant roses bloomed all about the garden there, and within the old chapel the choir practiced, and night fell, and the stained glass windows began to brighten. But no Discovery Tree.

It is of a piece with the history. For the explorers who followed Vizcaino over a century later were unable to find Monterey Bay or that tree. Portola, who led the mission expedition along with Junipero Serra, walked to San Francisco’s empty dunes and back, not knowing they’d passed it ‘way back there on the first march north.

Though on previous marches the Monterey Bay had not been recognized by these latter explorers, on a return reconnaissance they “got it”.

Of Monterey Bay they reported… “We now recognize it without any question… both as to it’s underlying reality and it’s superficial landmarks,” and “quite near, the ravine of little pools, the live oaks, especially the large one, whose branches bathe the waters of the sea sea at high tide, under which the Mass was said… by Sebast. Vizcaino.”

There at the Discovery site the great oak once stood for its span of three centuries, near today’s little white fence and historical marker.

I look back in time through an old photo of the site taken in 1890 or so, according to its caption. At that time the site was a much more open valley to the sea, bordered by a predecessor-fence which overlooked the disarray of branches of the Vizcaino oak in the photo.

On the white rail fence of that time is painted the words “Smoke Horse Shoe Tag Cigars.”

An eyewitness and creator of California history, Gen. Mariano Vallejo, who grew up in Monterey in the nineteenth century, was aware of the historic tree at the Discovery site. Controversy arose as to its authenticity- if a tree can be said to be authentic, which leads one to think that the tree wasn’t a big deal over the latter two centuries, just part of the landscape.

But Vallejo knew it as THE tree, and the story goes that eventually, when the land was to be improved, and the tree cut down and thrown into the bay waters, boats were sent to fetch it back.

So the Tree was “discovered” yet again- in the unlikely waters near Santa Cruz, and hauled back to Monterey.

“…Our arrival was greeted by the joyful sound of the bells suspended from the branches of the oak tree…”So wrote Fr Junipero Serra, on June 3, 1770.

“Kneeling down with all the men before the [makeshift] altar, I intoned the hymn… Then we made our way to a gigantic cross which was all in readiness and lying on the ground. With everyone lending a hand we set it in an upright position… I sang prayers for its blessing. We set it in the ground…” Then “raising aloft the standard of the King of Heaven, we unfurled the flag of our Catholic Monarch likewise. As we raised each of them, we shouted at the top of our voices: ‘Long live the Faith! Long live the King!”

This account certainly conveys the weight and heft of the ceremony at hand, as though by history’s eternal eyewitness- although the iconography of anguish is left unexpressed.

On a sunny morning in May, I spent an hour, thinking of these things, sitting in a pew a few feet from a fragment of the oak- now behind glass, worm-eaten but venerable.

There is a Mass at noontime there at Royal Presidio Chapel, which itself is a true founding site of Monterey. I am only an observer, but my observation was that there was a moment of reflection in the light of a modern time, and that Monterey was blessed to be lost and found again, and lost, successively. The empire has moved on.

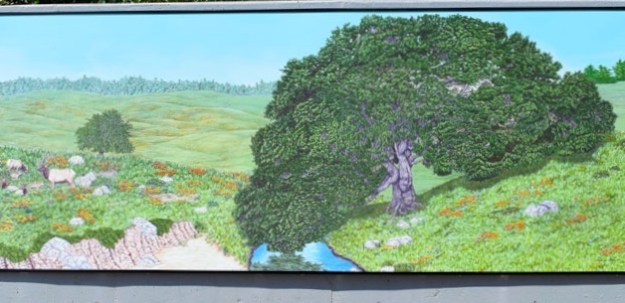

(Mural of Vizcaino oak, near the original site, with care for historical accuracy, by artist Stephanie Rozzo, 2015.)

Pingback: California Beginnings | jameskoehnsf's Blog