Rest With Me by the Shaking Earth

(California beginnings, one of many)

from notebook; San Francisco’s Great Earthquake/ Centennial

***

A memory stands between myself and the great earthquake and fire. The memory is of an old amusement park in Ohio called Geauga Lake Park. We’d go there in the middle of summer, in the absolute heat of July, and on Lake Park Days the park would be full. It was all wood and wire, with a roaring, rumbling roller coaster, and plank pavilions, with bumper cars with upright poles that snapped with live electricity. The wires cracked like a whip in the summer air.

The sounds of the amusement park, of the rumbling of heavy cars, the rolling barrel you ran through, the spinning wooden wheel you leapt upon and got thrown off of; the merry-go-round, too, rumbled heavily as it turned, but it was the cumulative clatter and wooden roar of the park I remember, the thrill and the electric snap of the rides draped with wire and cable, like some dangerously mad Edison experiment.

Suddenly, up out of the sky above the amusement park would come a massive storm. There was hardly any warning, but the trees would become a deep green, and the sky, purple, like an enormous bruise. Then the sky blackened and huge preliminary drops of rain fell, and then sheets of storm, and bolts of lightning and then- the whole crowd, as one being, began to head for the exit. Hundreds and hundreds of people hurrying, grabbing children, and rushing for the gate.

You’d look back through the walls of rain, stealing a last look back at the fragile crazy structure of the giant roller coaster, which stood against the dark sky, and framed the park- a contraption devoted to the semblance of danger- but suddenly faced with the real thing, you can’t believe that you actually got on that thing, and good thing you weren’t up there when the storm hit.

San Francisco has some of these elements of danger: it roars and rumbles and snaps. Its traffic howls through the tunnels under Broadway and Stockton. It rings and dings and tinkles with little bells. Its hills are skateboard dangerous. You drive without brakes half the time, and other half you’re on the cell phone and a wrong move can change everything. There are too many swinging doors and buildings aslant, and joints akimbo- and that’s on a normal day. At any time a bridge can become unhinged, a building sway like a hula dancer from the Sandwich Islands, and instantly the infrastructure is compromised.

I was thinking of these things last weekend on a peaceful April San Francisco day, when I was playing with my five-year-old friend Miles.

We’d spent the morning building a train town out of his wonderful wooden train tracks, with switchbacks, and sidings and parallel loops and still more switches and bridges. There was a farm in the middle to provide for the town, and a cow on the roof, and several trains chugging, by battery power, past the living room scenery.

In a moment of artistic pique, young Miles took off his shoe and lobbed it across train town and took out approximately two feet of track; the Infrastructure was definitely compromised. The track was twisted out of alignment, the cows went a-flyin’, and the trains in the immediate vicinity of the meteoric shoe were derailed, and tumbled into a multicolored pile of plastic. The Velcro shoe rested at a forty five degree angle against the twisted mass of train cars, and presumably some imaginary train-town news channel would cover it all live.

It was the centennial of the disaster and fire of 1906: what are the chances of San Francisco being hit with a tennis shoe?

Later that afternoon, Miles and his mom Gretchen and I drove up to the Randall Museum, ‘way up on the hill of Corona Heights. It’s one of the highest points in town, uplifted by a million years of San Andreas action down below in the subduction zone. The museum has displays of animals and birds, and activities for kids, and we’re having a good old time. They have a replica of an earthquake shack there, which I’d never seen.

The earthquake shacks were structures hastily provided for the camps of refugees from the Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906. I didn’t know the earthquake shack was right inside the museum. I was looking at the museum display of the seismograph there, and then walked through a doorway of a quaint little cabin right there inside the museum, and within was my friend Gretchen, sitting by the door, reading from a book, and there at her feet, her son Miles was listening to a story she extemporized, and she said, this is it, the earthquake shack.

I looked around at the space: enough shelter for a small family, a lantern on the wall, and my friends smiling up at me.

History is so easy-going sometimes. It’s quite deceptive. But I enjoyed the grace with which the city was opening the door to some deeper memories, collective ones, from one hundred years ago.

***

The park occupies high ground. It sweeps down a hillside in a dramatic way both visually and physically, offering a view of the entire city and its bridge to the East Bay, the San Francisco Bay at the far edge, and in the middle distance, the collapsed and devastated Mission District, now rebuilt on made land.

It would have been an advantageous place to witness the fire. You could see the whole thing from up there.

A photograph of Dolores Park on the morning of April 18, 1906, shows the park in the foreground, the great early morning fire in the background, a massive pall of smoke which looks to engulf both north and south of Market Street. All this in the distance beyond Mission High School, beyond the still, quiet park. A boy in the foreground is connecting with the photographer, but saying something, engaged as a witness. The park is nearly empty, but for these two witnesses, and a few figures clustered at the lower corner.

It is astonishing to see this quiet scene of witness in the empty park, for soon the rough grass and dirt will fill with refugees from the firestorm and from the demolished section of the Mission District. To me, it is a pleasant place of sand and swing sets. It is a familiar neighborhood playground for young Miles and his playmates, and, like Golden Gate Park, and Mountain Lake across town- places Miles knows well for slides and swings and little picnic lunches with his mom, of crackers and juice- these city parks were the first recourse for those that lost everything in the Earthquake and Fire.

Another photograph was taken from the high hill at the west side of Dolores Park, around the corner from my sister’s house on 18th Street. The fires south of Market have now spread in a dramatic swath through the entire Mission District. A pillar of fire above Market is now an appalling black smudge, a volcano of smoke, and now the park has perhaps a half dozen large white tents pitched on the high ground. In the foreground, a few feet from the photographer, a man walks by with a bedroll on his shoulder and an open umbrella. The tents and the progress of the fires could provide a timeline for the photo. The razor-back hill of the park conceals the low ground near Mission High, which doubtless contains refugees and makeshift camps by now.

In time, Dolores Park was crowded with refugees. Conditions were reported to be appalling, the fertilized ground now wet with rain, the makeshift camps thrown down anywhere in any space not already occupied. But the park seems to have provided at least some of the immediate exigencies of survival.

From Dolores Park, where cook fires on brick stoves heated soup or beans, one would have seen the ruined hulk of the downtown district still smoking. A photo shows a makeshift kitchen, right across the street from the high school, which was a relief station for refugees. There it stands, dug into the earth, a half-face camp with a roof of uneven planks, beside a row of tents, with a woman before it, stirring a pot by the fire, on its little stack of bricks, the caption reads “makeshift shelter dug out of the mud and manure in Mission Dolores Park.”

There were crowds at the Mission High relief station, “long lines and confusion,” according to one account. A Public Health Service physician called it “a deplorable state of affairs. There must have been more than 30,000 people living in shacks, tents, and other temporary abodes in this district. Those whose homes had been spared have to cook in the streets, as all chimneys, water and sewer connections have been destroyed by the earthquake.”

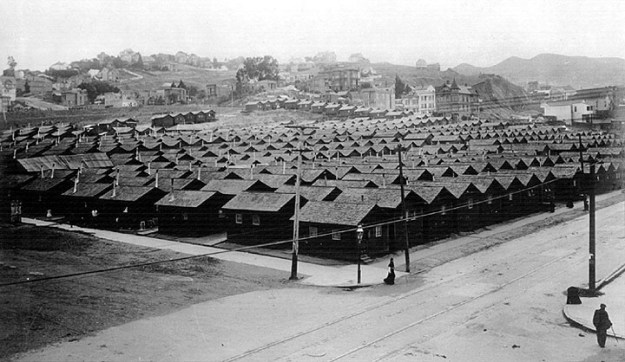

Within months, the makeshift camps of Dolores Park were cleared and reorganized into “Camp 29, Mission Park.” My stroll up 18th Street in the final block before Church, a few doors from my sister’s house, would have, had I been walking in 1906, led past a Dolores Park half-filled with earthquake shacks, an array of over five hundred of these, roof to roof.

There are photographs of Camp 29. The camp is a large square of earthquake cottages, and appears to be newly created; it is a picture of order. 18th Street is swept clean. A distinctly new street lamp stands at the corner of the cottage city. My sister’s partner Lou looked with interest at the streetcar tracks on 18th, now long gone. “Yes, that’s 18th Street, with the streetcar tracks…”

The official report and requisition allows for five hundred and twelve three-room cottages for Mission Camp 29. On October 19th it is established and could accommodate

1, 599 people.

***

A poetic text of the Great Earthquake and Fire exists in the public mind. Some can quote the familiar, chapter and verse: “The City Hall was a magnificent monument to greed and corruption; the refugees left the city in orderly and somber silence…”

Photographic scenes would translate well to stained glass, as would my favorite image, that of ladies and gentlemen atop the hill at Lafayette Park, standing with their backs to us, looking outward at the pillar of fire. One woman only turns away, and so, toward the present, toward us. Her head tilted slightly, reaching with fingertips toward her face. Is she turning to cough, or to burst into tears? Is she overcome by the enormity, about to faint, unable to communicate her emotion to others, as they watch, transfixed, as the first day’s fires take the city down? Does she know what her companions still don’t see, that the life they knew is coming to an end?

“… In three days the fires were out though the company safes were too hot to touch; cash bust into flame if safes were opened too hastily…”

That large print of Lafayette Square hangs in Green Apple Books, where I went to look for earthquake books. I stopped to stare at it a long while.

Prints and photos and blaring headlines on yellowed front pages are ubiquitous, tacked on walls at many bookstores around the city. They are the literary wallpaper of local culture, as instantly recognizable as the psychedelia of the Haight-Ashbury.

The San Franciscan Victoriana of Doom, and stereotypical art of the Sixties, the Beat Poets and jazz- these ghosts haunt the Great Earthquake and Fire, and the earthquake haunts them, though I can’t prove that. For me, they are all mixed together right now.

And to complicate things, when I look at a photograph taken on April 18, 1906, I feel that it is me that is the ghost. I am out of place, knocking on the glass, as if those watchers at the quake would turn and respond.

The veil is quite thin, now, between past and present. I wonder about bleed-throughs. We have mixed feelings about revisiting this history.

A native San Franciscan, commenting on 1906, told me that society is held together by very delicate filaments, right now. At the time of the photograph of April 1906, there were perhaps social codes which carried the society through the disaster. As he told me this, I looked in a book at the enormous photographic panorama of the ruins of San Francisco taken from air- from a “captive balloon” looking out over Nob Hill.

I floated there, ghostlike again, far above the ruined city, thanks to the aerial photograph, while my friend told me of his sorrows, his deep disappointment in society, in politics; his mixed feelings about the injustices and high-mindedness of the old San Francisco; and his view that the new San Francisco is covertly violent, gang-ridden, with a prevailing mindset which in the end devalues people.

T-shirts and blue jeans and road rage and the mindless pursuit of junk; the lack of courtesy, the lack of respect for others…My friend talked about these things as the Captive Balloon hovered in space above April 1906. As far as I could see, the ruins were still smoking, and, fascinated, I lived in two worlds for a moment, listening to the one of April, 2006, and looking intently-in real time- from

the air above San Francisco, in April 1906- at a San Francisco as barren as the moon.

So the photographs call to us, as if the San Franciscans of 1906 were to finally turn from the fire and look back, and engage us with a moment of contact.

jk

San Francisco

April 9, 2006