California beginnings, one of many.

Rock History: a Brief Survey of the Geologic History of San Francisco

***

“seismic gift”

ground has shifted.

Things might not be where you left them.

stuff toppled off shelves or at ominous tipping points

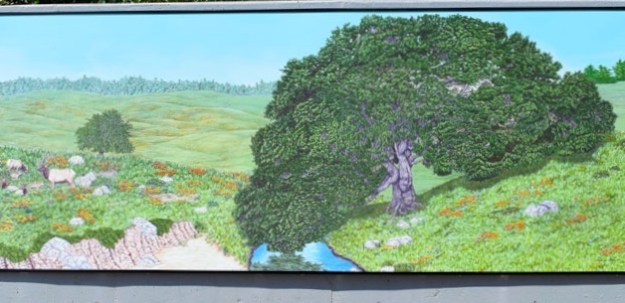

roots exposed

Rivers

changing course

or running backwards

That quiet place with the cool shade’s gone

Long view open to landscape light

It’s ok

Home has shifted in relation

Always there

Geology exposed

Outcropping to read

time capsule

you and I

Pipes have cracked water leaks

Rivulet promise garden

A building razed opens a walk

High above the strand below

One walker

our walk together

dogs still playing with the sea

Heart moon still there!

Roads sliding sideways

New alignments

Possible

You have to clean up this!

Throw out that

Never knew we had this

Damaged goods now

This is still good

My beloved still thankgod

Some look for meaning

Others get to work

***

Rock History: a Brief Survey of the Geologic History of San Francisco

San Francisco is dominated by its natural features, and famous for the tectonic drama of its earthquakes and fault lines. Yet its geologic history is, for many, still a puzzle. The explanation of its topography is still not widely understood, though geologists have made great advances in piecing together the story of Northern California’s creation and evolution.

From them we learn that the uniqueness for which Northern California is known has a geologic foundation, metaphorically speaking, for as the distinguished geologist and author Mary Hill wrote, Northern California was “pasted” on to the continent eons ago.

When geologists look at the rocks in San Francisco they see a chaos that comes from somewhere else, a melange that, until recently, utterly defied explanation. The region was never completely native soil; the fault lines undermined the sense of permanence and coherence that pervades the United States throughout the rest of the continent.

The geologic history of San Francisco is a constant presence, which, through dramatic landscape, connects the city’s inhabitants with the events that formed the western edge of the continent; it set the pattern for San Francisco’s metaphors of migration and creativity.

San Francisco topography: drastic hills, upon which multimillion dollar homes perch precariously, and twisted roads through colorful neighborhoods to views overlooking San Francisco Bay.

Beyond are the Marin Headlands, ancient, severe, connected to the city by what is still a most modern suspension bridge, at the Golden Gate.

From San Francisco’s central promontory, Twin Peaks, one can see in all directions an astounding view of low mountains to the north; to the west and southward, the rugged but regular shoreline of the Pacific Ocean.

Eastward, one looks down nearly a thousand feet and across an expanse dominated by the city below: seven square miles, with its abrupt hills and flatlands at sea level; and beyond, the huge, peaceful bay estuary with low-lying East Bay hills in the distance.

The beauty of San Francisco defies analysis, yet a unity underlies its mystique; it makes sense, in some undefinable way.

Looking down from Twin Peaks one sees a wonder, or an oddity, of the world. Part of the mystery is not logical, but geological. Geology, the study of rocks, and lithology, which attempts to explain sediments and formations, have everything to do with the creation of San Francisco and with its romantic allure.

Clues to the creation have long been known, but explaining the origin of rocks of San Francisco and the nearby Coast Range presented a challenge to geologists for nearly a century. Geologist Deborah Harden, author of a standard textbook on the subject, describes “the bewilderment of early geologists who encountered the rocks of the California Coast Ranges…the rules of classical geology were not sufficient for geologists to explain the origin of the rocks they saw…a baffling mixture of different rock types, jumbled together with enormous complexity.”

Eathquakes were known, of course, but the theory of plate tectonics was not. Though the topography of the Northern California Coast Range is an obvious geologic unity in its basic northwest configuration, following the Pacific coast, parallel to the peninsula on which lies San Francisco, the relations of all these natural forms was never understood until the theory of plate tectonics was advanced and effectively demonstrated in the 1970’s.

Plate tectonics deals with the solid structures, the fractured masses, which, combined, form the earth’s surface. The concept of crustal plates in motion was associated with a discovery that had to do with the spreading ocean floor: mid-ocean ranges, their sediments and volcanic rock were accumulated and displaced, and eventually driven into deep trenches beneath the continent’s margin, a process known as subduction.

These concepts underlie the theory, and explain the intriguing contiguity of the continents. Continents appear to be fractured fragments of one original whole, known as Pangaea, and the actuality of ocean floor spreading proved to be a force driving them apart over multi-millennia.

California may sometimes be imaginatively pictured on the western edge of this great Paleozoic supercontinent more than 235 million years ago, this from Richard P. Hilton, in tracing the geologic background of prehistoric California for a book on the state’s dinosaur past. Hilton explains that the very oldest rocks, of mineral limestone content and thus of marine origin, were found in the Klamath Mountains of the northernmost part of the state.

It is surmised from this ancient evidence, that California began as isolated, distant islands, which gradually migrated to the continent’s coast- which was then what we know as central Nevada. That is the starting point of our geologic history, ever driven by plate tectonics, the earth’s device for creating the ocean floor and continental crust.

The volcanic, ocean-spreading phenomena of mid-ocean, forces the matter of ocean plate into ridges, and islands like the Klamath feature noted above, and troughs, and deep trenches at the continent’s edge.

Forced by the spreading ocean floor in a dynamic called subduction, plate under plate, smashing rocks were jammed, uplifted, their stratified contents in horizontal levels now upended to the vertical to create the mountains of the Sierra Nevada.

So also did compression at the edge crumple and uplift the Coast Ranges, where San Francisco is situated, somewhat like a broken link in the mountains’ chain.

Thus the western edge of the continent was formed. Yet San Francisco’s geologic hills, plied by little cable cars, were still thirty million years away.

Research into San Francisco’s geologic history seems to fall into two categories: the age of rocks, and the forces that brought them into existence as landforms. The rocks are old; the forces that brought San Francisco into being are fairly recent occurrences, geologically speaking.

Geologists Hill writes, “It was not until about three million years ago- just yesterday in geologic time- that the Sierra Nevada began to rise as a great fault block.” Much is still unknown, but the rocks that make up the hills of San Francisco offer substantial clues as to age and origin.

The processes described above, of subduction and accretion of landmass, have delivered enormous blocks out of the substance of the distant sea floor to form our various neighborhoods.

Much of the ingredient rock that makes up the city is thought to be 100 million years old, that is, of the Mesozoic Era, the age of dinosaurs.

Subducted sediments were shoved beneath the continental plate, up to twenty miles below the earth’s surface, for one hundred million years of compression, heat, grinding, crushing metamorphosis, to form the characteristic rock melange of San Francisco. The basic rocks that make up the city are referred to by geologists as the Franciscan Assembly. It underlies the central block of the city and much of the Marin Headlands, as well.

The melange includes sea floor and sediments, sandstone and shale, all a kind of metamorphic mud, which was uplifted a million years ago as land. Known as greywacke, it is the hard rock of Telegraph Hill and Alcatraz. (Ted Konigsmark’s “Geologic Trips: San Francisco and the Bay Area.”)

Franciscan assemblage also includes basalt and chert. Basalt is synonymous with ocean floor, a volcanic, that is, igneous dark rock that emerges in cold ocean as stone pillows upon contact with cool sea water.

Clyde Wahrhaftig, a pioneering San Franciscan geologist, tells us that the enormous edifice of Twin Peaks is basalt, as well as a substance called chert. The basalt is probably associated with the mid-ocean spreading zone, as well as with volcanic eruptions on the sea floor’s moving crust.

Radiolarian chert is a component of much landform in the Bay Area. Chert is prehistoric, skeletal matter of microscopic marine life, which rained down on the ocean floor over millennia, and so provides scientists with clues as to a rock formation’s origin and age. Though the skeletal matter is tiny it compounds over time into large rock masses, with a characteristic, layered intricacy.

The fact that the Twin Peaks edifice is made of such ingredients as once made up the ocean floor 100 million years ago is astonishing, especially when one considers that the chert’s silica probably descended to the ocean floor near the equator. The College of Marin’s website “To See A World Project” describes the origin south of the equator; thus it migrated northward along with basalt to emerge as components of Twin Peaks and Marin Headlands.

Chert and basalt are associated with of the tectonic Farallon Plate, which traveled hundreds of miles to the San Francisco subduction zone. The whole process is s matter of 140 million years, from sedimentation to uplift, so that in standing on Twin Peaks, one stands upon a piece of Jurassic ocean crust, to look down on San Francisco.

San Francisco is also founded upon serpentine, another ingredient of the chaos/melange. The Golden Gate Bridge is anchored near serpentine, and the large outcropping which overlooks the Cliff House and ocean is serpentine.

Serpentine is California’s state rock and has an exotic origin far below the earth’s crust. It is a version of peridotite, of which the earth’s mantle is made. (John McPhee, Assembling California). This deep stuff runs in a band from Fort Point to Hunters Point; it underlies Potrero Hill and the foundations of the Mint near Church and Market.(Wahrhaftig) Far from the earth’s mantle now, it is everywhere seen in a diagonal band across the entire city.

Greywacke seafloor sediments; basalt lava and chert from the deep sea; serpentine from the earth’s mantle, and metamorphic rock from subduction zones; hundred million year old rocks make up the enduring landscapes of San Francisco.

The final element is dune sand, much of it from the ancient Sierra, associated with the most recent Ice Age, when the coast, due to the glaciers’ retention of large amounts of the earth’s water, was out beyond the Farallons, twenty thousand years ago.

The geologic story of San Francisco is a modern experience. For all the great age of its rocks, the landform is relatively recent. The accretion of land to the continent’s end, and the processes of plate- smashing and subduction that gave birth to the West Coast, were mostly subterranean phenomena, until perhaps two million years ago, when uplift occurred sufficient to create a landmass which tectonically evolved toward the SF peninsula formation. (Arthur D. Howard. Geology of Middle California)

Hauled northward by the San Andreas Fault over 28 million years, various migrating landforms finally parked in the vicinity: Point Reyes, and the Santa Cruz Mountain formation, driving along before it part of the San Francisco peninsula. A great river cut through the Golden Gate on its way to the sea beyond the Farallons. And starting about ten thousand years ago, the San Francisco Bay, once a forested valley, began to fill, flooded by the rising ocean waters as the ice age glaciers began to melt.

Research has revealed the probable age of the rocks and their provenance as migrants to the coast, but still to explain are the curious hills of San Francisco.

That Twin Peaks stands above the city is probably a case of what geologists call vertical displacement, due to forces of compression along a thrusting strike/slip fault. Blocks may fracture, and be upended. San Bruno Mountain, in South San Francisco, is such an uptilted block.

Once upended, the forces of erosion take over. Everywhere, rigid rock remains; the soft shales and sediments erode off; this accounts for the flat regions of the city. Thus we have prominent hills, with steep eroded sides, and stretches of flatland, and wind-blown Holocene sand.

A final piece of the San Francisco puzzle remains, provided by geologist Ted Konigsmark. The city’s geologic map is banded by parallel blocks, basalt, greywacke, serpentine, and metamorphic rocks: each a distinct layer of ancient rock, one terrain piled on another, in a sequence of time.

“Stacked like pancakes” on a tilted plate, these rock layers were thrust into the subduction zone at a steep angle. Then, presumably through uplift and erosion, the parallel pancake edges, now upended, were eventually exposed as the street levels of the modern city- and so, north to south along the cable car line, one travels through time.

Looked at from a distance, the low bay, the flooded peak of Angel Island-a “drowned” mountain- one gets the sense of the eroded past of the city. (Wahrhaftig).

The bay is shallow, four fathoms to shifted sand. The deepest point, over 300 feet, is near the Golden Gate, where ancient river flowed. The ocean was the gate of migration, by ships from the south, traveling below the equator the long journey around Cape Horn in the Gold Rush Era.

Just as the rocks migrated northward along a transverse fault millions of years ago, a migrating population sailed in over decades. Ships of the newcomers and the entrepreneurs encountered the natural conditions of coastal fog. Many ships had tragic encounters with geology, running aground in sediments at Ocean Beach, breaking up against serpentine at Land’s End.

Eventually foghorns and lighthouses appeared point to point, and cable cars, and chaos and creativity. All of this is connected to the geologic history of San Francisco.

Because of the chaos of rock, and the modernity of the landforms, very few fossils exist here; fossils just don’t make it here.

It is interesting to note, too, that the theory that explained San Francisco to the world, plate tectonics, also explained the world to itself. Far from being an isolated phenomenon, or California trend, or a lunatic fringe at the continent’s margin, the creation of California is a good example of how the earth itself creates.

And for geologists the theory, somewhat like the discovery of gold, changed the world.

outcropping, devils slide